Red-listing and Red-listed species

We mention ‘Red-listing’ a great deal in news posts and blogs on Protect the Wild, especially when it comes to issues around the shooting industry. But what is it?

Biodiversity loss is at last being recognised as having an absolutely critical impact on the survival of all life on the planet. Without animals, plants, and fungi there is nothing. Natural systems that arose in the stable conditions life evolved in, that provide the oxygen, water, and food we depend on, not only break down under biodiversity loss but could vanish altogether.

We can clearly see that biodiversity loss is taking place all around us: from fewer birds in our countryside to knowing megafauna around the world have been wiped away. That’s largely because we humans have severely changed more than 75 per cent of Earth’s land area. Some of the once incredibly diverse tropical forests are now nearly silent as insects have vanished, and grasslands (once one of the world’s richest biomes) are increasingly becoming deserts. On top of that 66 per cent of the oceans, which cover most of our planet, have suffered significant human impacts from pollution, massive overfishing, and now climate change. Huge areas of water are now ‘dead zones’, choked by algal blooms, deoxygenated, and otherwise almost sterile.

We are having profound and dire effects on life on Earth. How profound? You might have read a headline from Cop15 (the 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity) in Montreal that ‘a million species are threatened with extinction’. How did scientists reach such an enormous estimate?

It’s a figure largely based on data from the Red List of Threatened Species compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Quantify the threat

So we can see the impacts on wildlife all around us, but how do we quantify them? How do we actually put into figures – on a global and a local scale – what those impacts mean to the species we know and love (or indeed may never have even heard of)?

Through data collection, by comparing what was once present (‘since records began’) with what is present now, and uploading all that information into one easily accessed database. That database is the Red List of Threatened Species.

Established in 1964, the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species has evolved to become the world’s most comprehensive information source on the global extinction risk status of animal, fungus and plant species. Compiling the Red List has become a massive enterprise involving the IUCN Global Species Program staff, partner organisations and experts in the IUCN Species Survival Commission and partner networks.

The Red List is now an independent analysis of the health of the world’s biodiversity and a powerful tool to inform and catalyse action for biodiversity conservation and policy change. It provides information about range, population size, habitat and ecology, use and/or trade, threats, and conservation actions that will help inform necessary conservation decisions.

As of December 2022 scientists can be certain that 42,100 species are threatened with extinction. That includes 41% of all amphibians, the most threatened group of animals on the planet. They have been hit hard by habitat loss and the rapid spread of the chytrid fungus, an Asian species thought to have been introduced around the world by the wildlife trade. Australia recently announced that the Mountain Mist Frog had been declared extinct, adding to the list of ninety amphibia now thought to be extinct in the wild.

So where does that higher ‘million species’ figure come from then? It’s an extrapolation. It comes because just 28% of known species have been ‘threat assessed’ of which about 25% are threatened. Most species, therefore, haven’t yet been assessed (or probably even discovered), but based on what scientists already know about the global extinction threat and the scale of species loss in biodiversity hot spots like the Amazon it’s highly likely many more will be threatened with extinction. A million species threatened with extinction may be a guess, but it is a highly informed best-guess – and probably an under-estimate…

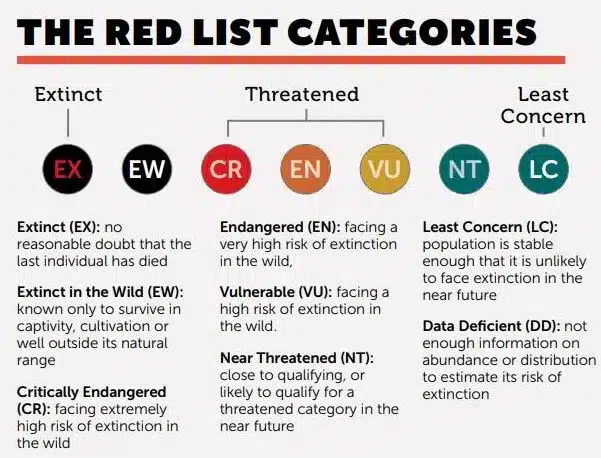

The Red List Categories

Just saying that a species – whether wild animal, plant, or fungus – is ‘threatened’ doesn’t really tell us very much though. It doesn’t tell us where scarce conservation resources should be prioritised, and it doesn’t reflect previous conservation work.

So the Red List is broken down into Categories which are in effect a measure of how close to extinction a species might be, ranging from ‘Least Concern’ (Green) through to ‘Critically Endangered’ (Red) and on to Extinct in the Wild (so still survives in zoos or private collections) and globally Extinct.

Once a species is listed the threat to it needs to be reassessed regularly of course. Situations change. More information might be collected, new populations found, or existing populations lost, which is why species might then move into different categories over time: if the threat has lessened the species may be ‘downgraded’, if the threat has become higher and more urgent it might be ‘upgraded’ (sadly generally more species are moved into higher threat categories than lower).

It’s worth bearing in mind that for some taxa very little is known, so their Red List status is very incomplete – fungi are one of the world’s most biodiverse groups, for example, but also the most under-represented taxa on the Red List with fewer than 650 species assessments currently published.

Red Lists in Great Britain

Many regions of the world have built their own Red Lists, and Great Britain is no different. In fact because of our history of amateur naturalists and an early drive to ‘count everything’ the state of wildlife here is amongst the best-known on the planet.

Red-listing here is overseen by an inter-agency working group co-ordinated by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) with members from Natural England, Natural Resources Wales and Scottish Natural Heritage. Data comes from charities and organisations including the BTO and RSPB, often collected by volunteers and grassroots organisations using citizen-science schemes that have systematically censused and surveyed at the same sites year after year.

That data is collected for everything from plants and fungi and birds to insects and mammals. That’s how we know that so much of our wildlife is vanishing and that, for example, a quarter of our native mammals are at risk of extinction, that almost one in five of our vascular plants are threatened, that half of British butterfly species are threatened, near threatened, or extinct, and that of 235 species of bird that regularly occur here 70 are now considered threatened.

The first UK Birds of Conservation Concern (BoCC) report, for instance, was published in 1996. Roughly every six years, experts from different nature and conservation organisations get together to update that report. Birds of Conservation Concern 5 – the most recent assessment of the status of all the UK’s 245 regularly occurring bird species – was published on 1st December 2021.

What it has to say is extremely concerning. Our bird life is suffering. The Red List of British birds published in 1996 had only 36 species. In the 2021 review it grew to 70, and now includes once familiar and widespread birds like House Sparrow and Starling which have suffered huge declines.

Eleven species were Red-listed for the first time in 2021, six due to worsening declines in breeding populations (Greenfinch, Swift, House Martin, Ptarmigan, Purple Sandpiper and Montagu’s Harrier), four due to worsening declines in non-breeding wintering populations (Bewick’s Swan, Goldeneye, Smew and Dunlin) and one (Leach’s Storm-petrel) because it is assessed according to IUCN criteria as Globally Vulnerable.

A report released in December 2022 was even more granular. It looked at Birds of Conservation Concern in just Wales. Many of the issues impacting birds in the UK as a whole – urbanisation, intensive agriculture, climate change – are of course just as pertinent to bird populations in Wales, and as expected the report mirrored the same trends. Importantly though producing a Red List for even a relatively small area allows for some legislative fine-tuning and localised responses.

What can we do?

So many suggestions have been made about what we can do. Everything from recycling, to eating less meat (we’d go further and say ‘no meat’), to not flying overseas. The list is endless. But what many commentators seem anxious NOT to say is that it is our fault. We have to own these problems because ecosystems don’t generally collapse (without a giant meteor strike anyway). Own them and fight back.

And when it comes to the Red List one place to start right here in the UK is to stop shooting Red-listed birds…

Did you know that the government still allows five Red-listed species to be also listed as ‘quarry species’ meaning they can be legally shot for ‘sport’ – including the Red-listed Woodcock pictured above (additionally the Amber-listed Common Snipe is still shot in large numbers)? Want more information – please go to Ban the Shooting of Red-listed species